The amazing ocean wildlife threatened by deep sea mining

From metal snails to ghostly octopodes, deep sea mining threatens to wipe out extraordinary, bizarre wildlife before we even fully understand it. A moratorium on deep sea mining is needed.

Less than 20% of the seafloor has been properly mapped. Before we even have a chance to explore and understand this vast environment, it may be threatened by the unsustainable exploitation of deep-sea mining. This extractive industry, still in its infancy, poses a major threat to wildlife and ocean ecosystems, including possible extinction.

In our open letter we call for the protection of ocean ecosystems as a crucial part of humanity's life support system - add your name here. Today, we take a deep dive to examine the wonderful wildlife living in these uncharted waters.

Life in the deep

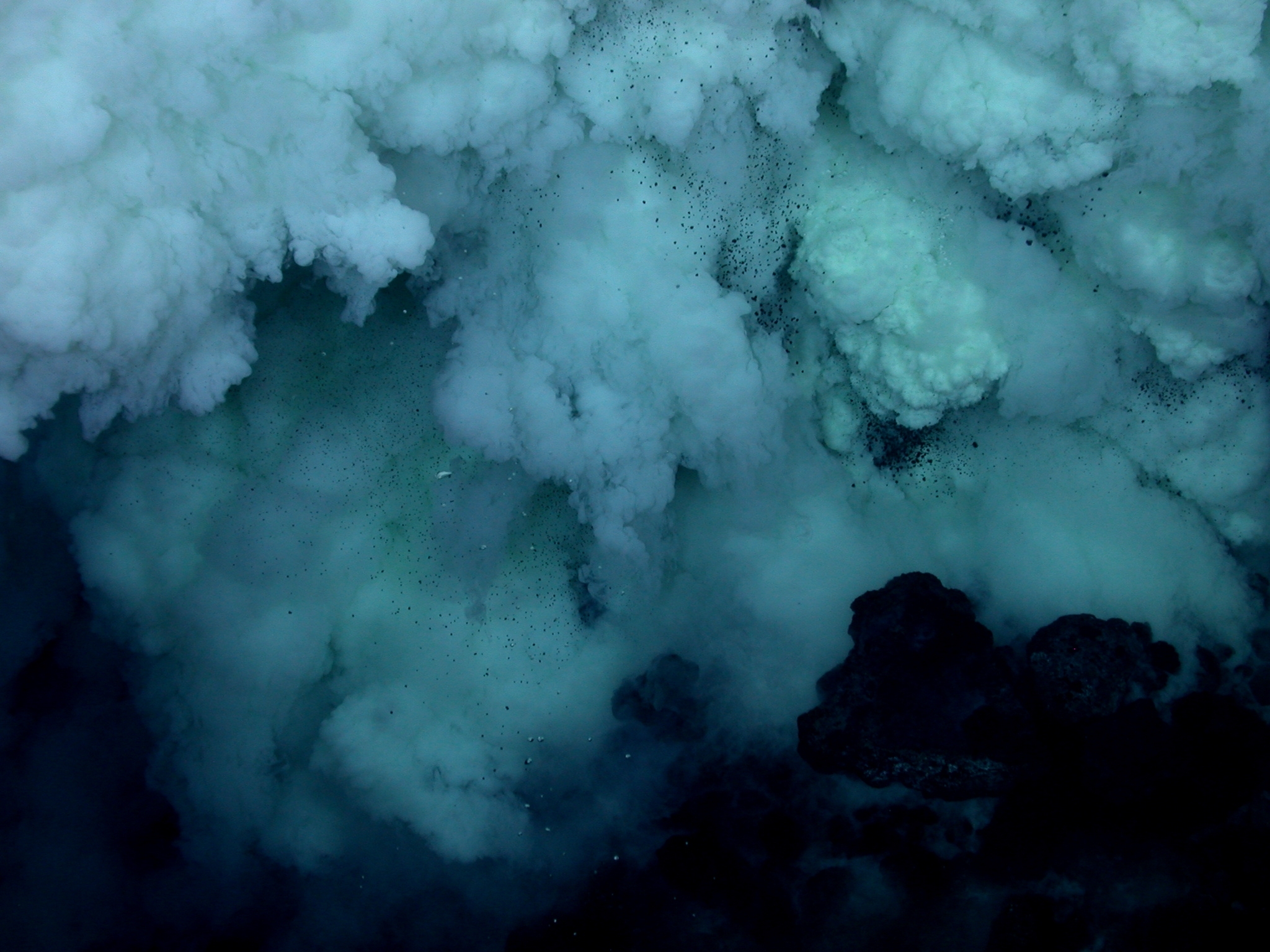

The deep sea is a harsh environment with little to no light, low temperatures and extreme pressure. Despite this, life exists here. At these depths, hydrothermal vents have become a biodiversity ‘hot spots’ for very special deep sea-dwelling animals which live in this remarkable environment.

Hydrothermal vents were first discovered in 1977 off the Galápagos coast and are significant in both the global carbon cycle and carbon storage. These vents are often found around active volcanoes on deep ocean ridges and emit hot, volcanic gases, which provides nutrients for living organisms.

These environments are often called ‘oases of the deep’ and the majority of their species are only found there – here are three special examples:

The scaly-foot snail, also called the iron snail, is found at depths between 2400-2800m in the Indian Ocean, and only on hydrothermal vents. This unusually large snail species is the only known living animal to use iron sulphide in its shell, and armoured plates on its foot. This armour, which makes them stick to magnets, may be used in defence against predators such as crabs and snails.

They do not actively feed, instead getting the nutrients they need through a symbiotic relationship with gut bacteria. So far, they have only been identified and sampled in three different locations, so more research is needed.

Zoarcid fish are found along the East Pacific Rise in the Pacific Ocean at around 2500m below sea level. They eat molluscs such as limpets, as well as gastropods and amphipods.

This enables other stationary species such as tube-building worms to settle, maintaining diverse and thriving marine life in and around hydrothermal vents.

Another resident of the East Pacific Rise, the hydrothermal vent octopus, is also a unique seafloor-dwelling species. As with the other species discovered at deep sea vents, not much is known about these ghost-like animals. Yet, one distinguishing feature is their lack of both colour and ink sacs.

They, and other Vulcanoctopus species with similar characteristics, have been dubbed ‘Casper’ due to their pale appearance. Because of the depths at which these octopodes live, and the absence of natural light, there is no need for the colour-creating chromatophores or ink that their surface-level cousins use as a defence mechanism.

Testing the deep

All these species, and more we are yet to even discover, are threatened by deep sea mining. This brings light and noise pollution, the loss of species communities, and damage to the vents themselves.

Future mining sites are predominantly located in international waters, and companies are not mandated to test newer technologies and larger equipment before use.

We do not and cannot measure the full extent of the damage and loss of species that deep sea mining would have on the marine environment, but we know the destruction is likely to be colossal.

By 2018, the International Seabed Authority had issued 29 contracts for the purpose of mineral exploration. With a space set aside in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the Pacific, and the Indian ocean for mineral exploration comparable to the size of Mongolia, commercial mining is expected to start in 2025.

A mining code agreement is set to be discussed later this year and may allow companies to apply for 30-year mining licences. This means that deep sea mining is becoming a major threat to our ocean.

How to respond

Governments and regulatory bodies such as the International Seabed Authority need to consider the real risks of deep sea mining. Join us in calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining to protect ocean wildlife, our climate and ourselves.

- Sign the petition here

Image of a scaly-foot snail courtesy of Kentaro Nakamura et al, reproduced unchanged here under a Creative Commons License.

Image of a zoarcid fish courtesy of Citron, reproduced unchanged here under a Creative Commons License.

Image of an octopus courtesy of NOAA, reproduced unchanged here under a Creative Commons License.

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF