Today marks the 36th anniversary of one of the world’s worst industrial accidents, a tragic and avoidable disaster that exposed half a million people to toxic gases leaking from Union Carbide India’s pesticide factory in Bhopal, India. Almost 4,000 people were killed immediately and hundreds of thousands were left with acute medical conditions and many later died of their horrific injuries.

Despite that dreadful warning, the use of pesticides around the world continues to be normalised. It is, for some, an extremely profitable business: today the agricultural pesticide industry is worth US$60 billion and consumption of pesticides has risen from 1.8 million tonnes in 1990 to almost 3 million tonnes today.

As Bhopal showed, pesticides are extremely dangerous poisons, often derived from, or related to, chemical weapons like Sarin gas or Novichok. These lethal chemicals not only kill target pests, but accumulate in the food-chain, devastating biodiversity by killing pollinators, birds, mammals and fish.

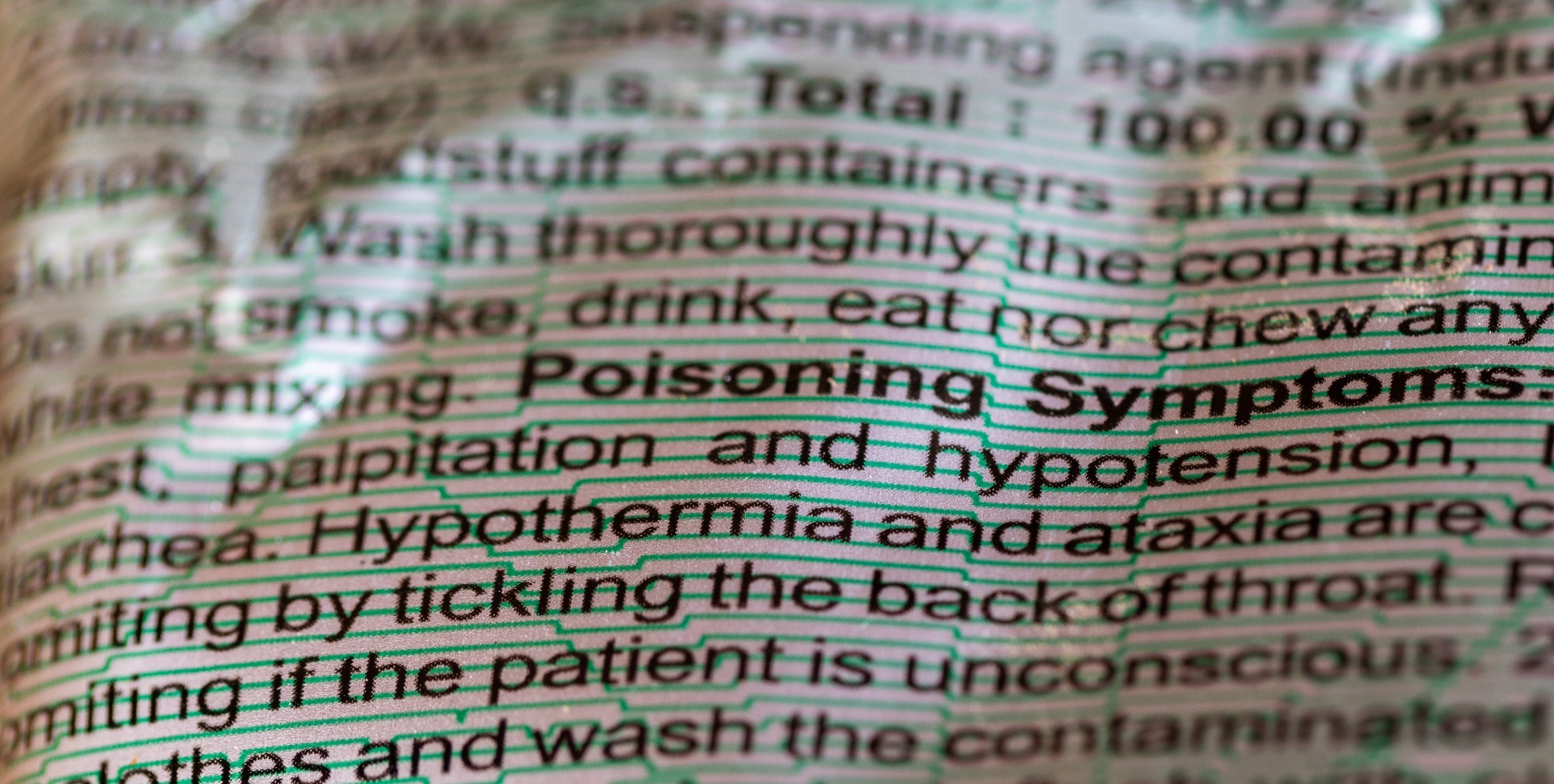

The medical dangers to humans are equally alarming: it has been estimated that around 800,000 people in developing countries have died due to pesticide poisoning since the onset of the Green Revolution in the early 1950s. Other estimates suggest that pesticides are responsible for as many as 200,000 deaths per year. Pesticides have been proven to cause cancer, foetal abnormalities, hormonal imbalances, reproductive difficulties, mental retardation, intestinal ailments and immune-system deficiencies.

Pesticides have been proven to cause cancer, foetal abnormalities, hormonal imbalances, reproductive difficulties, mental retardation, intestinal ailments and immune-system deficiencies.

Pesticides are so widely used that residues are now commonly found in every corner of the globe: ‘persistent organic pollutants’ include the pesticide Endosulfan, which has been found in samples from vultures to beluga whales and in remote regions including the Himalayas and high Arctic.

Despite being subject to a global ban from agricultural use decades ago, DDT is still commonly detected in soils and in today’s foodstuffs like beef and eggs. A recent report from EFSA, the European Food Safety Authority, discovered that that nearly half (47.8%) of its 91,015 food samples contained quantifiable traces of pesticides. Around a third (29.1%) contained traces of more than one. The US Geological Survey has detected Glyphosate in more than 75% of rain samples across the American Midwest. Residues were found in 27 out of 109 samples of bread sold in the UK.

Toxic cotton

Of all the crops across the world, cotton uses the highest quantity of pesticides. Although cotton only accounts for around 2.3% of global arable land, it uses just over 16% of global insecticides. In many countries, those figures are even more stark: in India, cotton is grown on 5% of arable land, but it is responsible for 50% of the country’s pesticide usage.

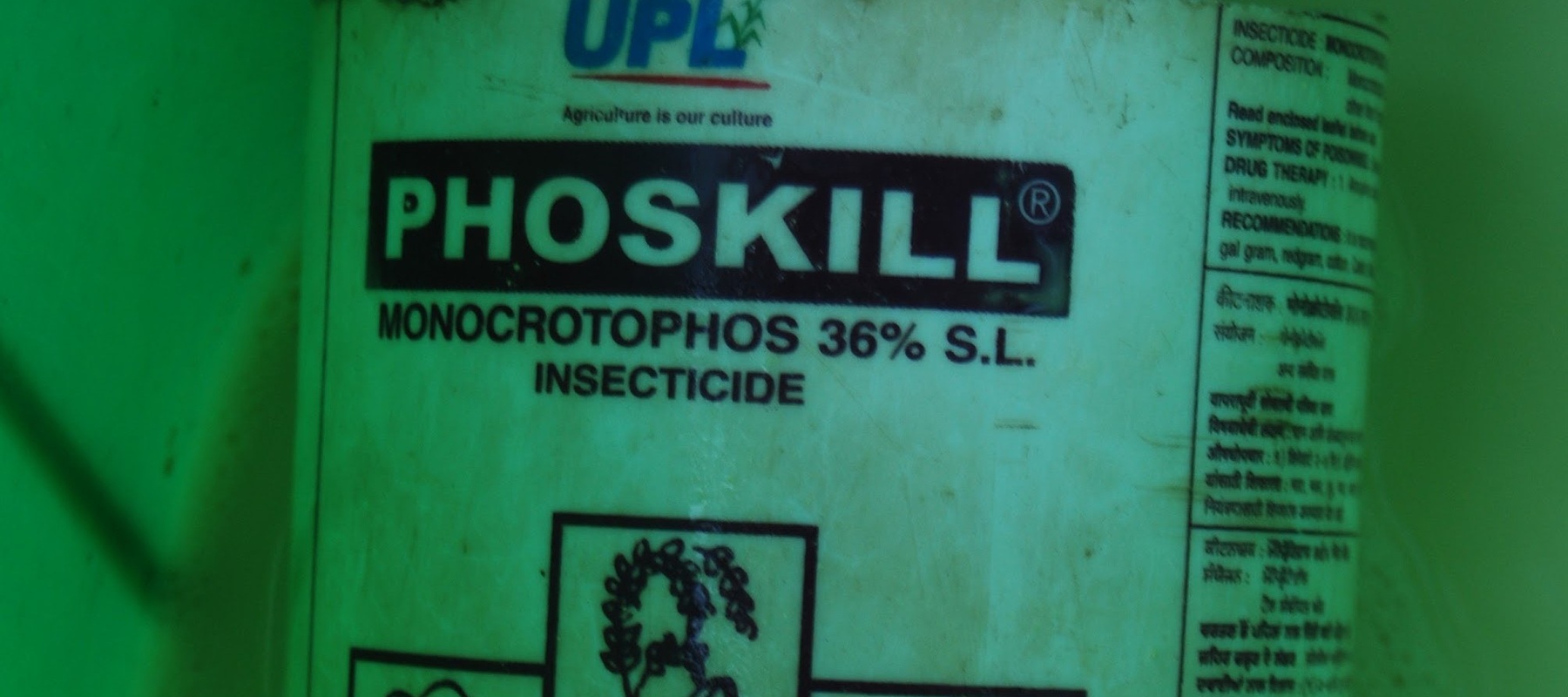

It’s not just the amount of pesticides used in cotton which is problematic, but also their toxic potency. Cotton uses a higher percentage of ‘highly hazardous pesticides’ (or HHPs) than any other crop. Whereas globally only 25.8% of pesticides used on cereals, and 43.5% on rice, are HHPs (according to the Pesticide Action Network’s definition), in cotton the equivalent figure is 69.1%.

Although cotton only accounts for around 2.3% of global arable land, it uses just over 16% of global insecticides.

Technological advances in the past 25 years were supposed to combat cotton’s pesticide addiction, but they have had the opposite effect. Monsanto’s genetically modified cotton was patented in the mid-1990s to combat pest invasions by the cotton bollworm. Called ‘Bt cotton’– created by the insertion of genes from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) into the cotton plant – it effectively turned the plant itself into a pesticide. The uptake of Bt cotton was extraordinarily wide: by the 2012/13 growing season, after only 15 years on the market, Bt cotton and other biotech varieties were planted on 23 million hectares of cotton plantations, 68% of the total global coverage.

But there were unexpected consequences: secondary pests – aphids, thrips and whiteflies – filled the vacuum left by the cotton bollworm, which soon became resistant to the Bt cotton anyway. By 2018, in India (the world’s largest cotton producer), the per hectare costs of insecticide use were 37% higher than in 2001.

In the USA, cotton-growers were also planting herbicide-resistant cotton. This led to vast increases in the use of herbicides since they could now be sprayed without precision or concern: by 2011, an estimated 96% of all US cotton was genetically designed to be herbicide-resistant, and herbicide use had increased from 2.1 kilograms per hectare in 1996 to 3.0 kg/ha in 2010. It’s been estimated that herbicide-resistant crop technology in the USA alone led to a 239 million kilogram increase in herbicide use between 1996 and 2011.

Doomed to fail

Aside from the environmental and health hazards associated with that additional usage, it was also irrational: the reliance on repeated applications of one herbicide – Monsanto’s Glyphosate and its generic imitators – resulted in weeds becoming resistant to its effects. According to the Weed Science Society of America, by 2012 there were over 5.7 million hectares (14 million acres) of US soil overrun by 22 different types of herbicide-resistant weeds. One agrochemical firm now calculates that herbicide-resistant weeds may be seven times more prevalent, covering 40 million hectares of American soil.

Farming in this way – spreading poisons which eradicate biodiversity, but which soon fail because the target pest develops resistance - is nonsensical: it makes a handful of corporations very wealthy but exposes both farmers and consumers to grave dangers. Studies have shown that cotton, like foodstuffs, contain traces of these toxic chemicals: in 2015, research from the University of La Plata, Argentina, found that 85% of cotton used in a medicinal or sanitary setting (gauze, swabs, wipes and tampons) contained Glyphosate. Research from Zimbabwe, in 2019, detected Endosulfan in processed cotton at almost double the allowable ‘maximum residue levels’.

Pesticide use in cotton is a particular concern as the crop has various important by-products that enter the food chain. By weight, two thirds of the harvested cotton is not lint that makes fabric, but seed that is crushed and used as cooking oil and margarine throughout the developing world. The meal and hulls, rich in protein but poisonous to humans, are used as feed for livestock – usually to cattle, poultry and fish. This can create a process known as bio-magnification, whereby pesticide concentration increases as it travels up the food chain.

It makes a handful of corporations very wealthy but exposes both farmers and consumers to grave dangers

Step up the fight

Now is a crucial period in the battle against pesticides for a number of reasons. The EU is considering closing a glaring loophole which allows EU companies to manufacture and export pesticides which are banned within the EU: Paraquat, for example, has been banned in Switzerland since 1989 and in the EU since 2007 because it has been repeatedly linked to increased risk of leukaemia, lymphoma, skin and brain cancers, Thyroid disease, end-stage renal disease and pulmonary oedemas. Exposure to Paraquat also leads to a two-fold increase in risk of Parkinson’s Disease. And yet the Swiss firm, Syngenta, reportedly exports, on average, 41,000 tonnes of Paraquat per annum from its UK plant in Huddersfield. The German firm, Helm, also exports paraquat to developing countries.

European producers are knowingly exporting toxic chemicals that are banned from use here, selling instead to markets where environmental protections and enforcement and lax, and where farmers are unaware of the risks to their health.

Pesticides are extremely dangerous poisons, often derived from, or related to, chemical weapons like Sarin gas or Novichok.

The UK also faces a major decision regarding pesticide usage. As the country negotiates new trade deals in the aftermath of leaving the EU, there is a very real danger that food safety standards will lapse: the EU’s policy towards pesticides is precautionary – the onus is on the manufacturers to prove they are safe. In the US, the onus is on regulators to prove they are harmful. It’s certainly possible – some would say probable – that the far laxer US approach is likely to be imposed on any British trade deal, including an increase in the ‘maximum residue levels’ allowed within our food.

But even in the USA the tide is turning against pesticides. In June this year, the chemical giant Bayer (which acquired Monsanto in 2018) agreed to pay out over US$10 billion to settle claims brought by tens of thousands of Americans who have suffered Non Hodgkin Lymphoma and other cancers which they blame on Glyphosate (‘Round-Up’) and other Bayer herbicides. That followed the announcement by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in March 2015 that it considers Glyphosate a “probable human carcinogen.” The weedkiller is also widely believed to be an endocrine disruptor, meaning that it messes with human hormones and can cause reproductive difficulties and birth defects.

It is vital for the European Union follow up on the EU Commission’s promise to close the pesticide loophole in its ‘chemical strategy’ within the new Green Deal. We also urge the UK Government to maintain the most rigorous pesticide standards in any future trade deals following Brexit. Consumers, too, have a vital role to play: in choosing to buy organic cotton, they can support and promote a form of cotton cultivation which renounces the folly of pesticidal farming and protects farmers, their families and the natural environment upon which they depend.

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF