“It was 3:30am when I jumped. There were two possible outcomes – we would escape, or we would be killed. But it made no difference. We were working to serve them, and we would not continue. So I jumped into the sea.”

These are the words of a man we will call Ko Myo, although that is not his real name. He was a Burmese worker trafficked onto a Thai fishing boat, and then trapped at sea, at the mercy of his abusive captain.

Ko’s story is sadly common. Many migrant fishers are trafficked onto vessels and once out at sea, far from authorities, they are subjected to a kind of hell. Investigations by the Environmental Justice Foundation have uncovered cases of slavery, debt bondage, insufficient food and water, squalid living conditions, physical and sexual assault and even murder aboard fishing vessels from all over the world.

This photo essay shows some of the faces and tells some of the stories of those who have suffered this fate.

Burmese migrant workers in Thailand are easily identified by their white boots. Tun Myint* was caught by police after escaping from the fishing vessel he had been trafficked onto. Instead of helping him, the officers sold him back to the same company. In March 2017, the company owner was jailed for 14 years for the trafficking of migrant workers onto fishing vessels.

Thai trawlers transfer their catch to a mothership off a remote island chain in the Andaman Sea.

These unmonitored ‘trans-shipments’ allow illegally caught fish to be mixed with legitimate catches, masking its provenance. It also means trafficked, slave crew can be kept on board for months or years at a time, making escape almost impossible.

Burmese migrant workers await repatriation at a shelter for victims of human trafficking in Songkhla, southern Thailand. Many thousands of workers are trafficked onto fishing vessels around the world every year, as fish stocks collapse and vessel owners seek to maintain profits by using underpaid or even slave-labour.

I have been working on the boat for three or four years.

EJF communicates with a trafficked worker aboard a Thai fishing trawler during a trans-shipment at sea. The worker provided coordinates for the remote site where the fortnightly trans-shipment took place, allowing the team to document the transfer and alert authorities.

A 2009 United Nations Inter-Agency Project on Human Trafficking study found that 59% of trafficked migrants interviewed aboard Thai fishing vessels reported witnessing the murder of a fellow worker.

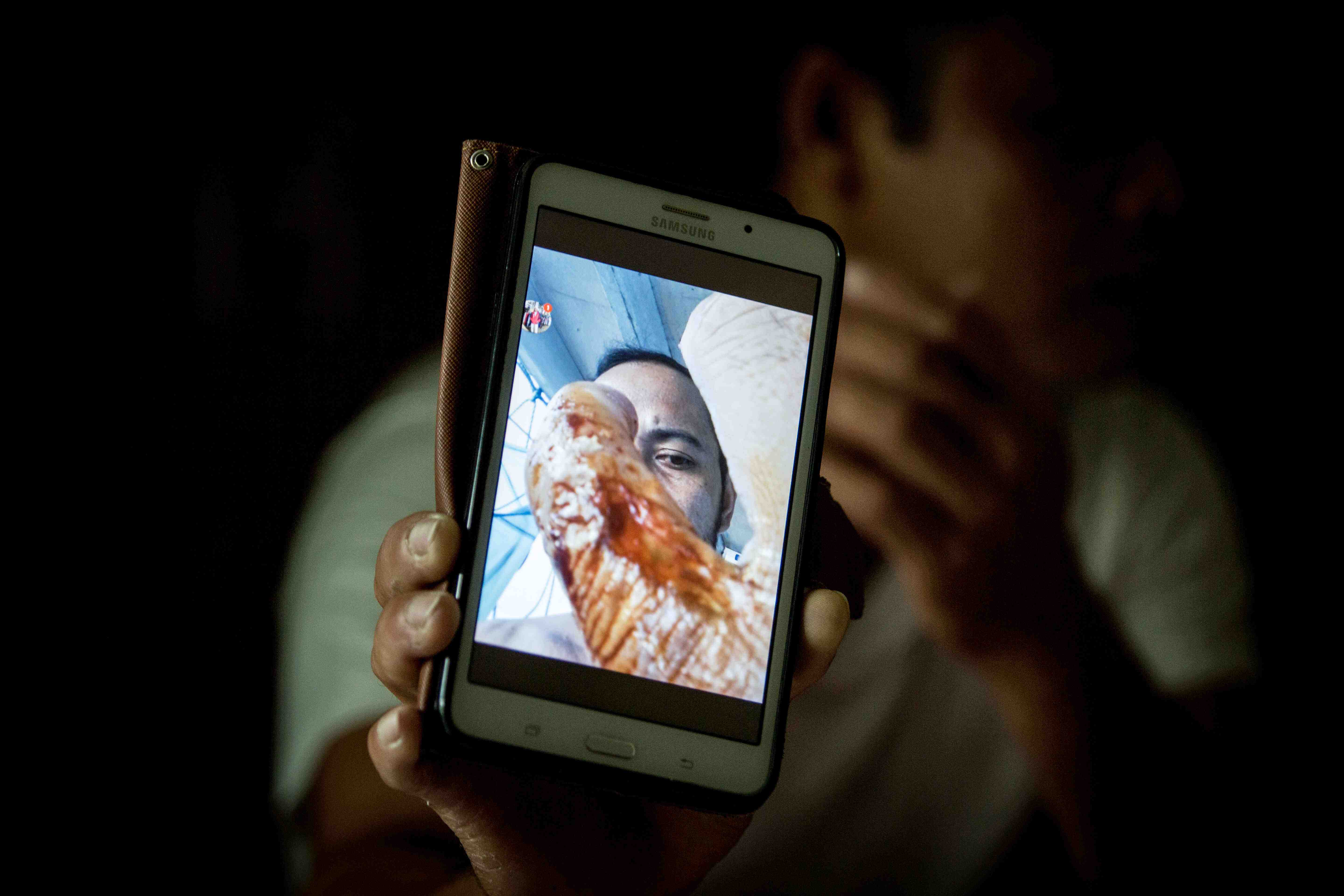

Marwen* was trafficked onto a Taiwanese fishing vessel in 2016. Pictured here in a Taipei shelter for trafficked workers, he shows pictures of injuries he sustained and living conditions aboard the fishing vessel. He was made to continue working for days after his accident and has suffered permanent damage to his hand.

Workers report being coerced into signing contracts written in Chinese that they are unable to read. They must borrow money from brokers to cover travel, medical and administration costs. This is repaid from their meagre salaries over the course of their contracts, which can last for years. As such, they are victims of debt-bondage and feel compelled to continue working, regardless of how they are treated or the condition on board the boats. Many fear for the safety of their dependants at home, who are sometimes threatened if debts are not paid.

I was afraid, afraid of death. If I die, who will take care of my kid and my wife?

Supri from Indonesia, was on board a Taiwanese vessel when he was locked in a freezer by the captain while he was still wet from the shower.

“It was so cold inside. He did it on purpose. I shouted ‘Captain! Captain!’ Begging him to open [the door]. I kicked at it, but still he kept it locked. I was afraid, afraid of death. If I die, who will take care of my kid and my wife?”

On the same trip, Supri was electrocuted with a stun gun by a fellow crew member under orders from the captain. The tool is used to kill fish, and the shocks left Supri weak and in pain.

The individual stories are horrifying, but it is the systemic nature of the abuse that must be tackled. The first and most effective line of defence is surprisingly simple. Transparency.

If governments published details of what vessels are operating legally on the one hand and the punishments they hand out for human rights abuse at sea or illegal fishing on the other hand, seafood buyers would have a clear record to use for their purchasing decisions. If transferring fish between boats at sea was banned, (or very carefully monitored) unscrupulous companies would not be able to keep workers at sea, unpaid, for months or years as they are shifted between boats.

The stories these men told us are harrowing, but they must be heard. Consumers, processors, retailers and policymakers, everyone has a part to play in ending this destruction of ocean ecosystems and abuse of people. Together we can bring fishing out of the shadows.

This essay was originally published by Fair Planet.

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF