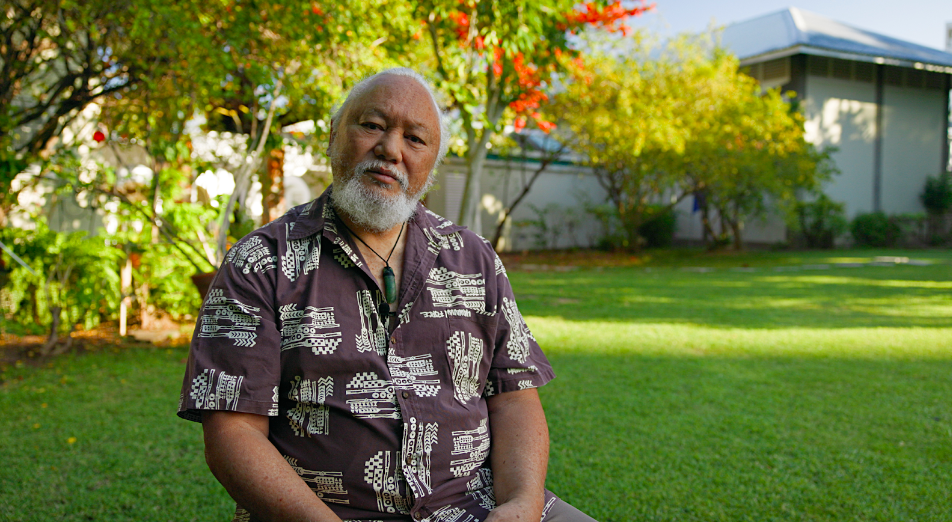

Alanna Matamaru Smith is the director of the Te Ipukarea Society (TIS), a non-governmental environment organisation based in the Cook Islands working to protect our Ipukarea, which translates to ‘our heritage’. She has a Bachelor of Applied Science in Environmental Management from Otago University New Zealand, and a Masters in Conservation Biology from Victoria University, New Zealand. She also won Miss Cook Islands in 2017. She recently attended the 28th Session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in March with the Indigenous Pacific Islander delegation.

In the Cook Islands we are surrounded by our huge Pacific Ocean, which we call Moana Nui o Kiva. It is a core part of our identity. Our country, which is 99.99% ocean, is made up of 15 islands. Naturally, we look to the ocean for our food, culture, and heritage. For too long the voices of Indigenous Pacific Islanders have been excluded from conversations about the ocean, despite our deep knowledge of the sea and its importance for our livelihoods.

Most Western culture is unsustainable, as it relies on harmful practices and resource extraction for profits, with little to no consideration for a healthy future. At Te Ipukarea Society, we work to help ensure the protection of our heritage, our Ipukarea. We do not own the land or ocean – we are just the caretakers for future generations, and therefore we must do all in our power to protect and maintain a sustainable environment.

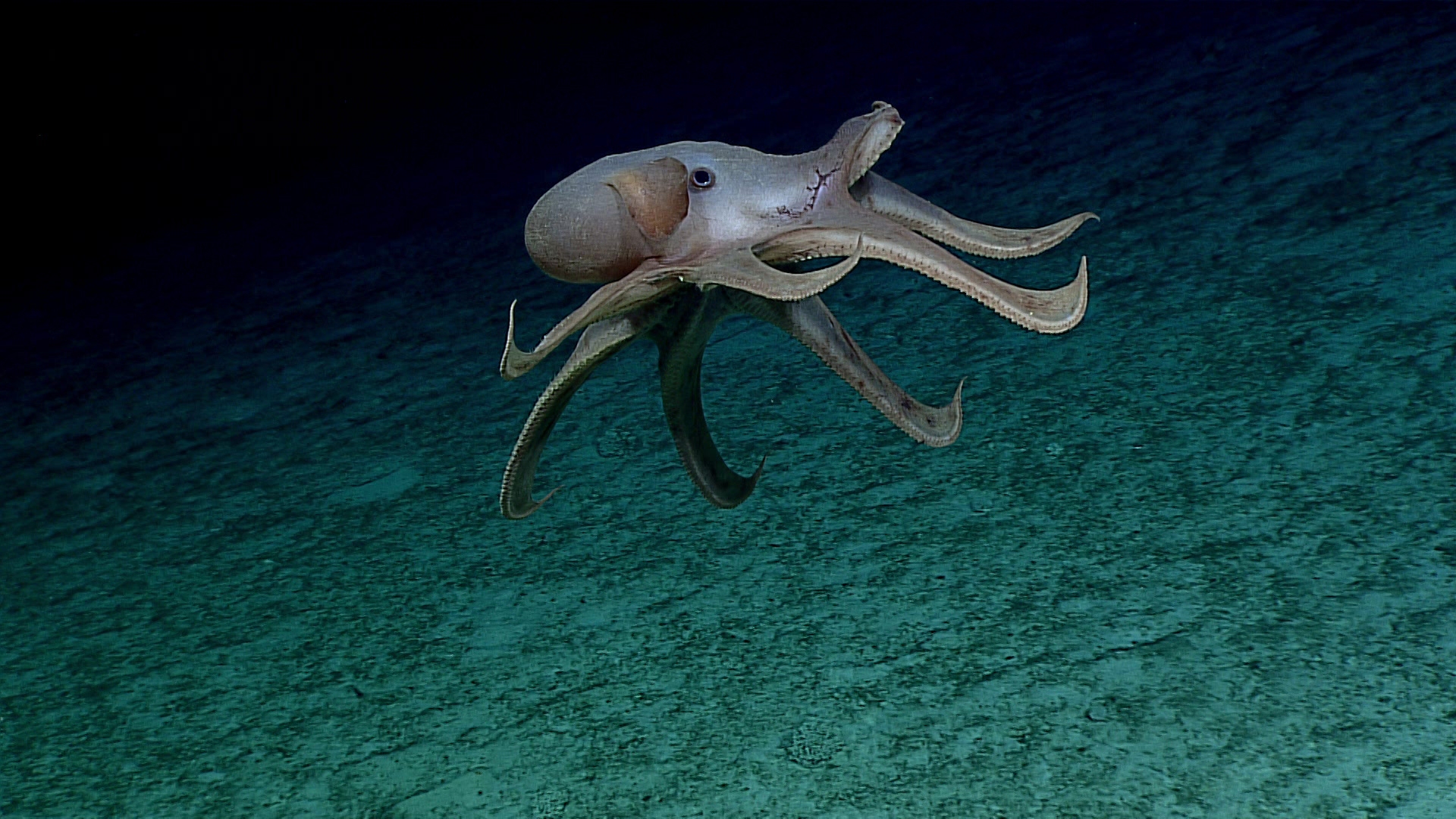

Polymetallic nodules exist in our Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), so the Cook Islands government has an interest in navigating the potential of deep-sea mining. They have passed legislation, the Seabed Minerals Act 2019, to bring commercial deep sea mining closer to being a reality. Just last year, we entered a five year phase where three mining companies have been issued licences to undertake exploration within our waters. The results of these explorations could have a massive impact on Cook Islanders, and the Pacific Region.

The people of Cook Islands, particularly those in the outer islands, are heavily reliant on their environment and fisheries. Fish provides 50-90% of animal protein consumed by coastal communities across many Pacific island countries and territories, with per capita consumption exceeding the global average by 3-4 times or even more.

While there is still much research to be completed, initial investigations into the potential impacts of deep sea mining make it clear there is substantial risk if it goes ahead. For example, research has been done into how toxins contained in sediment plumes from deep-sea mining activities are at risk of accumulating throughout the food chain. It has also been found that the outer layer of the nodules contain radioactive elements that could be released during the mining process. These risks alone should be enough to pause plans to move forward with deep-sea mining so we have time to research its impacts. Any effect on our tuna fisheries would be very detrimental to our day to day living as Polynesians, so we cannot take this potential threat lightly.

If this fishery resource, which has long supported our livelihoods and our economy, is damaged, we would be confined to importing even more Western products that would shift us away from our customs and towards a more unsustainable way of living. We are already experiencing this now, importing plastic products that we cannot recycle, along with electronic waste which sometimes gets buried or burned in fire pits – both of which have massive environmental and health impacts. We must act as the custodians of our natural resources that keep us alive and self-sufficient as much as possible.

There is also a massive lack of knowledge about the environmental risk of deep-sea mining. Our government is in favour of deep-sea mining, and the information they make public is skewed towards its financial benefits, while spending little to no time on what the risks are.

The narrative coming from mining interests that we need these minerals to be energy efficient is not valid – the energy transition is only needed because of industrialised countries’ historic and ongoing fossil fuel emissions. Technology is constantly evolving to a point where we may no longer have to rely on metals such as cobalt, found in the polymetallic nodules, for the green energy transition. Deep-sea mining would only perpetuate a long history of industrialised nations exploiting the environment, walking away, and then placing much of the burden of risk on Pacific Islanders.

The culture in which we live is unsustainable – if we keep ripping and taking from our planet without giving anything back, we will destroy our home. We must create circular economies, and invest in technology and innovative solutions like battery and metal recycling, and more energy efficient transport systems that make deep-sea mining unnecessary. This change must happen globally.

I attended the ISA conference in March as a member of the Indigenous Pacific Islander delegation. After 27 years it’s the first time our NGO and Indigenous voices have been heard at the ISA meeting. It is disappointing that it took so long for our perspective to be included, but we hope we will continue being supported to attend. However, after my experience observing the discussions at the conference, I wonder whether the views of Cook Islanders and other countries with a commercial interest in deep sea mining are accurately reflected by our state representatives.

Pacific Islanders are seeing the ramifications of constant consumption and extraction in sea-level rise, wildlife loss, polluted beaches, and much more. The food security and culture of Cook Islanders are at risk, yet communities know little about these high stakes – how can our leaders push this forward if those who will be most impacted are not informed in a balanced way?

Knowledge must empower people, but this cannot happen if the government leaves informational gaps. This is why Te Ipukarea Society works to educate the community, including those hard to reach on the outer islands, so they can have informed opinions about this issue that will directly affect their lives, particularly with regards to food security and their future livelihoods in their island homes.

We are caretakers of the environment we live in, charged with ensuring these resources are around for our future generations to also benefit. A significant amount of time is still needed to ensure more independent environmental research takes place to better understand the many underexplored mysteries of our deep sea. I call on our leaders to take on this responsibility to pause progress on deep-sea mining now.

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF