Sleepwalking into disaster with deep sea mining

Despite widespread opposition from around the globe, we may be on track to see the first deep sea mining within a year. Governments must stand up for the ocean and impose a moratorium.

The rush to exploit the deep

The deep ocean makes up 90% of the marine environment, but it is in peril. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is currently negotiating regulations for how deep sea mining will be governed once it begins, despite fierce opposition to this new frontier of ocean exploitation.

This follows the Pacific nation of Nauru triggering an international agreement in June last year meaning the ISA must finalise regulations for proposed exploitation within two years, and that regardless of what is agreed mining must be allowed to start then. This means that the clock is ticking; the negotiations happening now will govern what, if any, rules regulate the deep sea mining which can now begin as soon as in a year’s time. There are now 31 licences for exploratory mining, and full-blown exploitation licences could be granted next year. This would be devastating for ocean ecosystems and our climate.

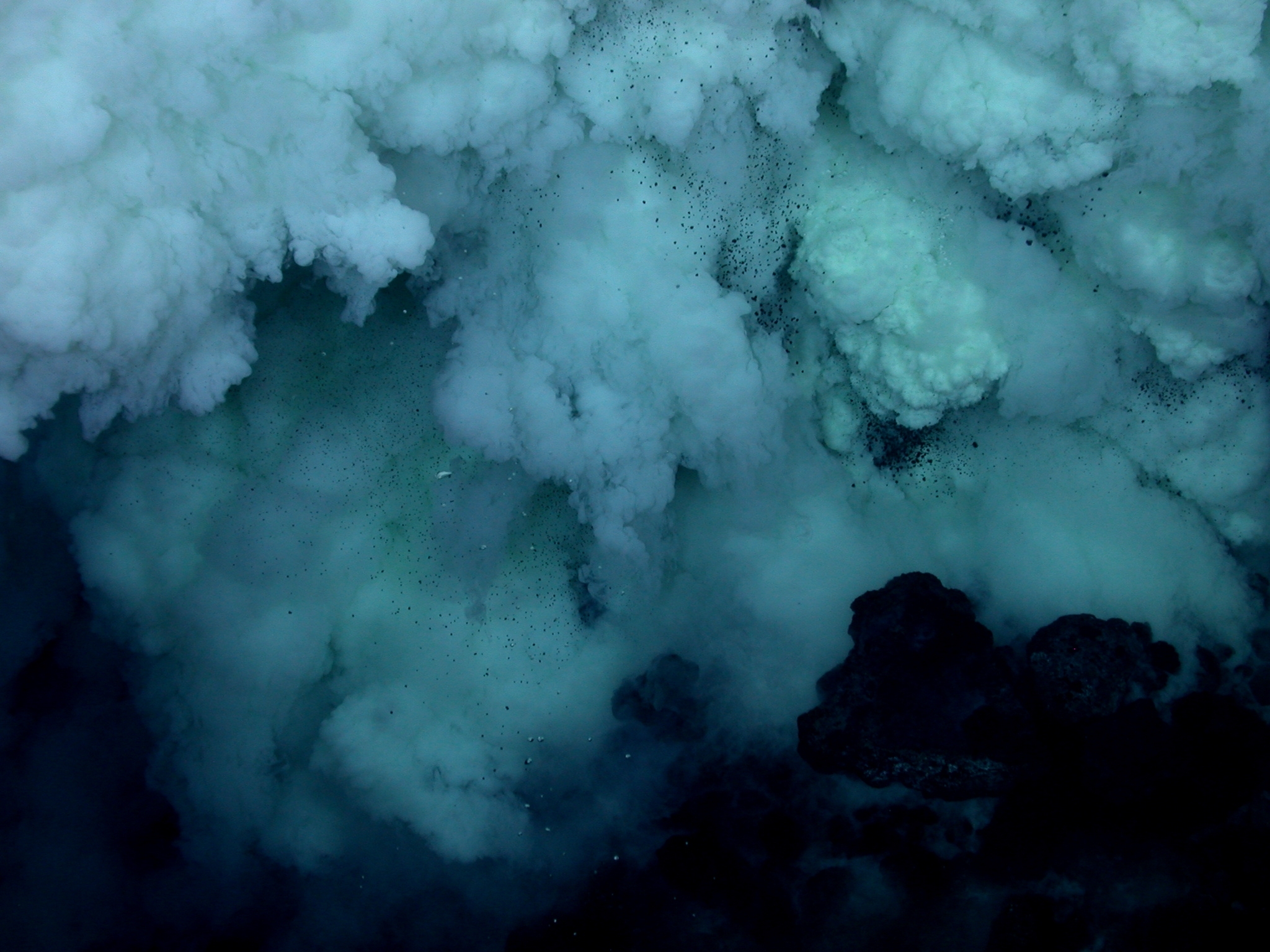

The deep sea is vital in the fight for our survival against climate breakdown. The ocean absorbs 90% of the heat produced by our carbon emissions and its ecosystems provide a number of life support systems, such as carbon sequestration and nutrient recycling. For example, hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the seafloor are not only biodiversity hotspots for remarkable deep sea-dwelling animals – including the fascinating, and endangered, “iron snail”, but also hotspots for carbon capture.

However, the deep sea is now being valued by some for its resources, particularly metal-rich mineral deposits. Copper, cobalt, nickel and manganese are lucrative, making deep sea mining a potentially attractive venture. Pro-mining groups argue that deep sea mining is necessary in the climate battle, as the metals could be used for electric car batteries and solar panels. But this argument has narrow logic, based on continual consumer growth that doesn’t take into account the very real solutions provided by a circular economy and/or recycling to provide us with the metals we need to manufacture batteries and solar panels.

Mining the deep sea to provide us with the metals needed to supply the “green economy” is nonsensical when we consider the destruction that would be wrought on the deep sea, arguably the world’s largest carbon sink.

A lack of transparency

The ISA has not shown the necessary leadership to protect our ocean, as they have granted a deep-sea mining exploration contract for every application they received, covering 1.5 million square kilometres of seabed. There is a dramatic lack of transparency in their decision-making process, as contracts approved and annual reports of these projects are confidential, and all meetings of its legal and technical commission happen behind closed doors.

The relatively small sums ISA member countries would receive from deep sea mining royalties are not enough compensation for the price humankind as a whole would pay for the damage caused by deep sea mining. The main beneficiaries would be a few wealthy individuals and investment companies, who would retain most of the profits.

At the ongoing ISA negotiations, Chile’s delegation said that they "can’t agree with the task being undertaken in a way as to prioritise a contractor starting work running counter to interests of humanity", Germany pointed out that “the vast majority of species habitats and ecological processes are still unknown in the deep sea” and the Federated States of Micronesia indicated they see unregulated deep sea mining as incompatible with their national-level ocean conservation commitments, drawing attention to the “unitary” nature of the ocean. Several nations have raised concerns about the financial sustainability of mining companies and the rush to exploit the deep ocean more quickly than detailed assessment would require.

Widespread opposition

At the recent UN Oceans Conference (UNOC) in Lisbon, there was a flurry of action to denounce deep sea mining and call for a moratorium on deep sea mining. The President of Palau, Surangel Whipps Jr., announced the launch of the Alliance of Countries Calling for a Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium. Fiji and Samoa were the first countries to join the Alliance.

Chile has called for a 15-year extension for the formulation of deep-sea mining regulations. President Emmanuel Macron of France also spoke out against deep sea mining, arguing that a legal framework was needed to stop it from going ahead and for more funding for research into our oceans. A Member of the European Parliament, Marie Toussaint, co-launched a declaration signed by 216 other parliamentarians from 47 countries who are committed to making the moratorium a reality, and who have called for a reform of the ISA.

Companies such as Volvo, the BMW Group, Samsung, Google, Volkswagen and more have also committed to not using minerals sourced from the deep ocean. 653 scientists so far have also called for a pause to deep-sea mining. It is overwhelmingly clear that experts, politicians, companies and the public do not want this unnecessary, unproven, highly destructive exploitation of our ocean to go ahead.

Despite this, we are currently sleepwalking into a disaster. At present, the regulations are still being formulated and exploitation contracts could be granted next year. Deep sea mining could wipe out ocean ecosystems and unique species before we even have a chance to understand them. Governments must stand up for the shared future of humanity, and for life on Earth, and impose a moratorium on deep sea mining now.

Cover image courtesy of NOAA, reproduced here under a Creative Commons License.

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF