Conventional cotton is the world’s ‘dirtiest’ crop - using more chemical pesticides than any other major crop.

Cotton accounts for just 2.4% of the world’s cultivated land but uses 6% of the world’s pesticides and 16% of its insecticides - and this addiction to toxic chemicals leaves a trail of death and destruction in its wake.

Every time we choose to buy cheap, inorganic cotton clothes we contribute to this toxic chain. But it is impoverished farmers who pay the real price.

Many farmers in developing nations are sold the lie by multinational pesticide companies that toxic chemicals are essential to grow cotton.

This is especially acute in India, the world’s leading producer of cotton. Every year a large number of India’s 5.8 million cotton farmers are poisoned by their exposure to pesticides. Many have died, while many more continue to suffer with chronic illnesses.

It does not need to be this way. India is also the world’s leading producer of organic cotton, providing more than 50% of the global organic cotton supply. But currently only 1% of Indian cotton is organic.

As major consumers of Indian cotton, we can help shift this dynamic.

This March, an EJF team travelled to India to speak with people directly affected by India’s addiction to pesticides - and those trying to lead India towards organic cotton farming. These are their stories.

LIVES TORN APART

In the heart of India's central cotton belt, 2017's cotton season brings back particularly painful memories.

Within just a few months, dozens of farmers died from pesticide poisoning and about a thousand more were hospitalised. The main hospital in rural Yavatmal was overwhelmed and ill-equipped to deal with the escalating situation. Witnesses describe patients having to share beds or sleep on the floor.

It was during this traumatic summer that Sandeep Madavi lost his father, Devidas.

What happened to my father should not happen to anyone.

Sandeep

“He was suffering a lot… he was unable to walk," Sandeep remembers.

Devidas writhed in pain so violently that he had to be bound to the bed. After two weeks in intensive care, he died.

Devidas was paid 200 rupees (just over £2) to spray the pesticides that led to his death. His wife Mangala says that poverty leaves Indian farmers little choice but to gamble with their lives using pesticides.

He only went spraying that year because he couldn’t get any other work. If he didn’t go spraying pesticides… then my husband would be alive.

Mangala

About 200,000 people die every year from pesticide poisoning worldwide. Chronic exposure to pesticides has been linked to cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, hormone disruption, developmental disorders and sterility.

THE BATTLE WITH PESTICIDE COMPANIES

2017 may have been an especially bad year. But this is not about one year or one place.

Pesticide poisonings occur wherever they are used - and equally consistent is the struggle to make pesticide companies accountable for their damage caused by their products.

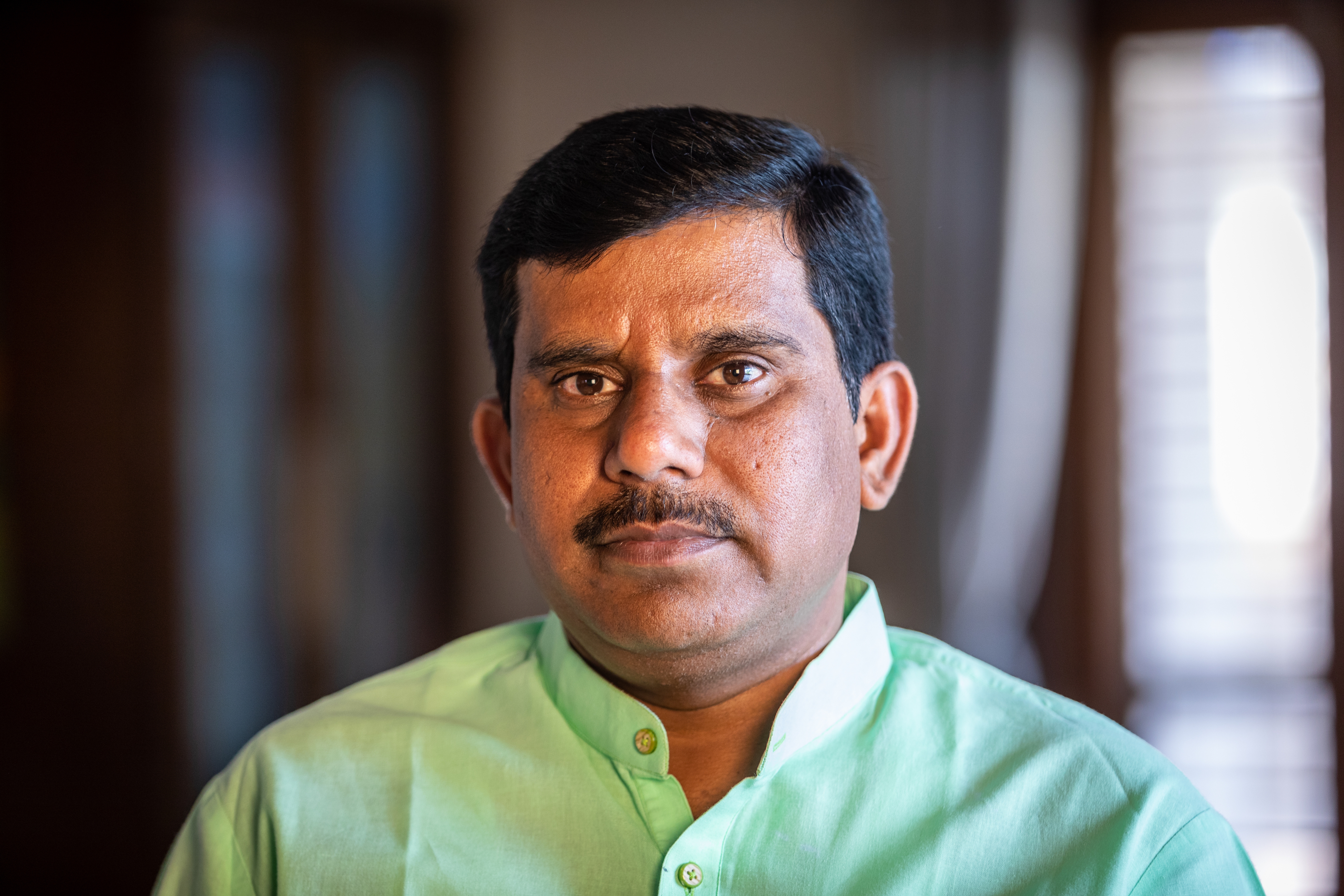

Horrified at the scale of pesticide poisonings, Devanand Pawar founded the Maharashtra Association of Pesticide Poisoned Persons (MAPPP) to help victims claim compensation from pesticide companies.

The companies say that spraying pesticides brings you a good crop, but we only see deception. Our people are losing their lives. We are angry about it and now we are fighting against it.

Devanand, farmers’ rights activist

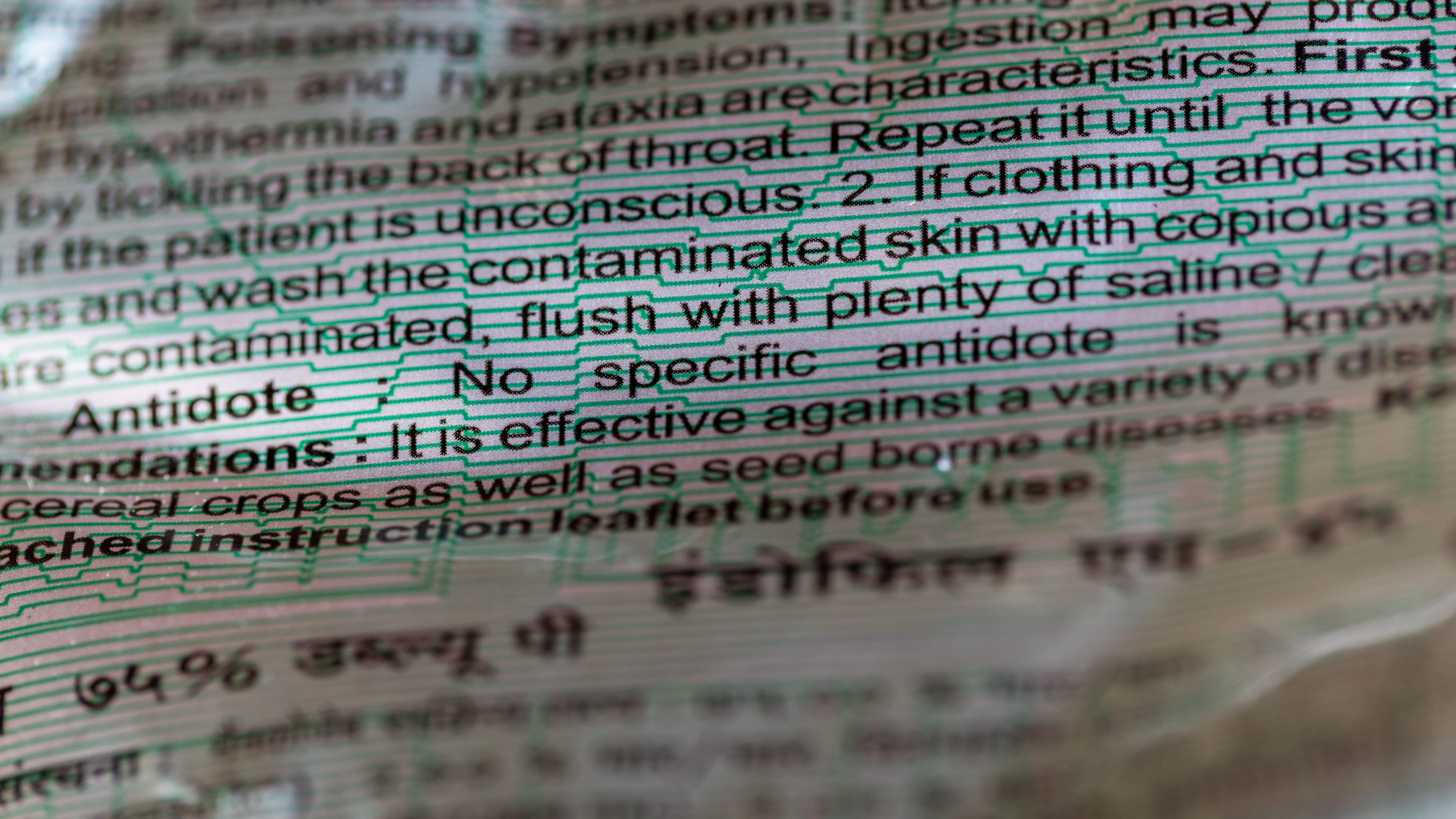

“When multinational companies sell their pesticide products, their protective directions are written in such small letters... they know very well that farmers from the villages are illiterate,” Devanand adds.

“They don’t even understand English. That’s why companies take advantage of it. And we just want to show that these companies are cheating us.”

Many pesticides with no known antidote continue to flood the Indian market. Often warning labels are not written in local languages.

CHRONIC PAIN

For the survivors of acute poisoning, the suffering often continues long after they leave hospital.

Many live with lifelong health issues and are unable to work.

I vomit 2-3 hours after I eat a meal.

Satish, who suffers from stomach problems and pain in his hands and legs, three years after being temporarily blinded by pesticides.

In India, it’s typically men who spray pesticides. But women aren’t immune to the dangers.

“I was watering the pesticide-sprayed crops [when] suddenly I started feeling nauseous,” Sindhu recalls. “My nose started running, I felt dizzy, my eyes were burning."

I was scared…I have two children. My daughter is disabled, I have to look out for her.

Sindhu

Sindhu no longer goes near pesticides. But her husband still does.

“I think about [the risk] always,” she says. “But we don’t have a choice. If we don’t do farming, what can we eat? What can we do in the future?”

THE PUSH FOR ORGANIC

Sindu is far from alone in feeling trapped.

So strong is the stranglehold of pesticides in India, many cotton farmers feel they have no alternative.

But a growing organic movement across the country is aiming to educate cotton farmers and provide them with a way out. The promise is clear - organic farming uses no harmful pesticides, it’s better for the environment, and it delivers more money directly into the hands of farmers.

If everything in farming is done organically, it can guarantee a better healthy lifestyle for everyone. It is important that we do what is best for our environment. After all the problems we faced with chemical farming, we must go forward with organic farming.

Usha, health worker and organic advocate

We need your help in this. If you feel that pesticides can cause diseases and put lives in danger [...] do not wear these [inorganic] cotton clothes.”

Sahebrao, organic farmer and anti-pesticide activist

OUR CHOICES MATTER

Most organic farmers don't have the power to take on the dominant pesticide-cotton market alone. That's why many have banded together to form collectives up to 5,000-strong, to help them compete.

Now it's up to us to do our part and buy the organic cotton they produce.

The choices we make as consumers have consequences that shape our shared world.

This gives us the power to shape the future like never before. We can choose to remain part of a supply chain that forces farmers to risk their lives to produce our clothes. Or we can choose to support the organic cotton movement that can sustain rural communities and ensure their right to a healthy life and a secure natural environment. Let’s move to fashion that looks good and does good.

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF