A new industry is threatening our ocean: Deep-sea mining risks destroying fragile marine ecosystems, precious habitats and undiscovered species, with potentially devastating consequences for our planet’s health, local and indigenous communities, and future generations.

Hidden by murky governance and conflicts of interest, we cannot let companies strip mine the seabed against the opposition of people, scientists, governments and many of the companies they claim they would be providing for. We urgently need to stop deep-sea mining before it has even started.

Deep-sea mining has to be stopped

The deep sea is still a pristine ecosystem, largely untouched by human activity.

It covers 65% of the Earth's surface and makes up more than 95% of the Earth’s biosphere. We all depend on it; the deep sea underpins all ocean ecosystems and plays an important part in the global carbon cycle.

Yet deep-sea mining – which would likely become the largest mining operation in history – would significantly disturb the delicate environment of the deep sea, with devastating consequences for our ocean, wildlife and the people who depend on both.

This is despite an almost total lack of understanding of just how serious the impacts would be, as well as fierce resistance from scientists, businesses, financial institutions, civil society, and an increasing number of states. Without more research, we simply cannot know what would happen, but we know it would likely be devastating.

EJF urges the international community to stop the rush towards any deep-sea mining activity and the international legal framework that is to govern it – the so-called Mining Code:

Stop deep-sea mining. All efforts should be made by the international community, in particular governments and corporations, to prevent mining operations in the deep sea. The depths of the ocean contain some of the most biodiverse, undisturbed, and vulnerable ecosystems on the planet. All scientific evidence gathered so far indicates that the consequences will be devastating for the deep-sea ecosystem, with immense risks for the health of the ocean as a whole and the benefits it can provide for people. Moreover, the climate emergency requires a critical examination of the potential impacts of deep-sea mining activities on the carbon cycle.

Scale up investment in deep-sea research with a view to protecting our ocean and climate. Critical gaps in our understanding of the deep sea prevent fully informed, science-based decision-making. The international community should support and promote scientific research on the deep-sea environment, with a view to improving our understanding of its functioning, its rich biodiversity and the ecosystem services it provides, including its role in the carbon cycle.

Reform of the International Seabed Authority (ISA). There is an urgent need to improve transparency and accountability of decision-making at the ISA – including through access to information and opportunities for meaningful public participation in the deliberations of the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) – and to address potential conflicts of interest through an independent periodic review process. In the absence of a Scientific Committee and in light of the ISA’s clear mandate to protect the marine environment, the composition of the LTC should be reformed to significantly increase expertise in marine biology and conservation. While these reforms can be implemented immediately and will help to address major shortcomings in governance observed to date, there is a need for a broader overhaul of ISA structures and procedures, including the criteria for electing members to the ISA Council and the procedure for approving applications for exploration/exploitation. Until credible, transparent and independent governance structures for managing the deep-sea commons are in place, no legitimate decisions about deep-sea mining can be made in the interests of all humankind.

Ensure the protection of deep-sea biodiversity. In line with Target 3 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, governments must designate at least 30% of the ocean – including national and coastal waters and the high seas – as ecologically representative, fully or highly protected marine areas (MPAs) by 2030, and provide the resources necessary to ensure they are monitored and fully enforced. Prompt agreement on a strong, comprehensive and legally binding High Seas Treaty with high standards of protection for marine ecosystems in areas outside of national jurisdiction, including through the establishment of effective MPAs in the high seas, is critical for achieving this.

Invest in and implement circular economy solutions. Both governments and industry must stop following the “take, make, waste” economic model, and transition urgently to a circular economy. This should include promoting and implementing large-scale electronics reuse and recycling programmes and the extension of product life cycles, and investing in energy efficiency and public shared transport systems to reduce the need for resource-intensive energy infrastructure. Investment should be increased into technological innovation, such as the development of less resource-intensive batteries to support the clean energy transition. The introduction of mandatory obligations for battery recycling and collection, end-of-life requirements, targets for the recovery of metals and extended producer responsibility will further reduce demand for virgin metals and align our needs with planetary boundaries.

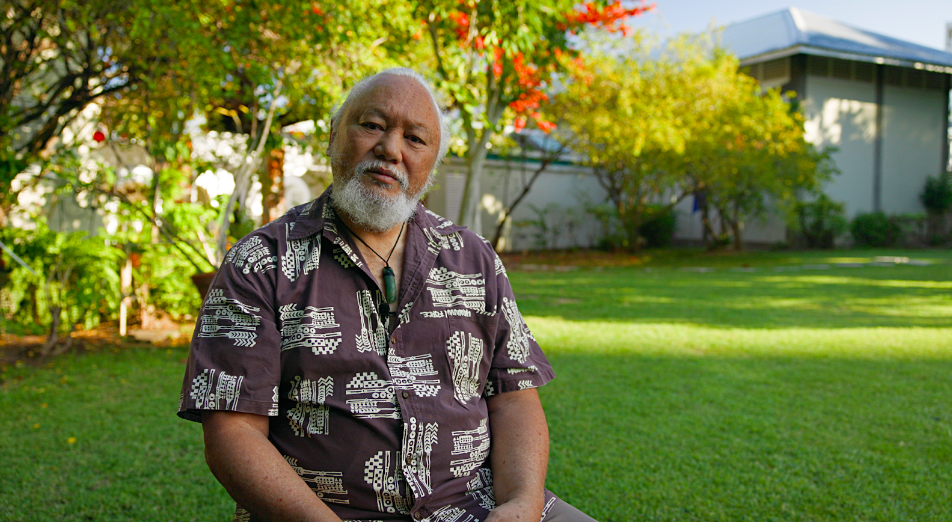

Powerful voices and testimonies

We share the perspectives of Indigenous people, scientists, civil society, and experts, voicing their grave concerns about deep-sea mining:

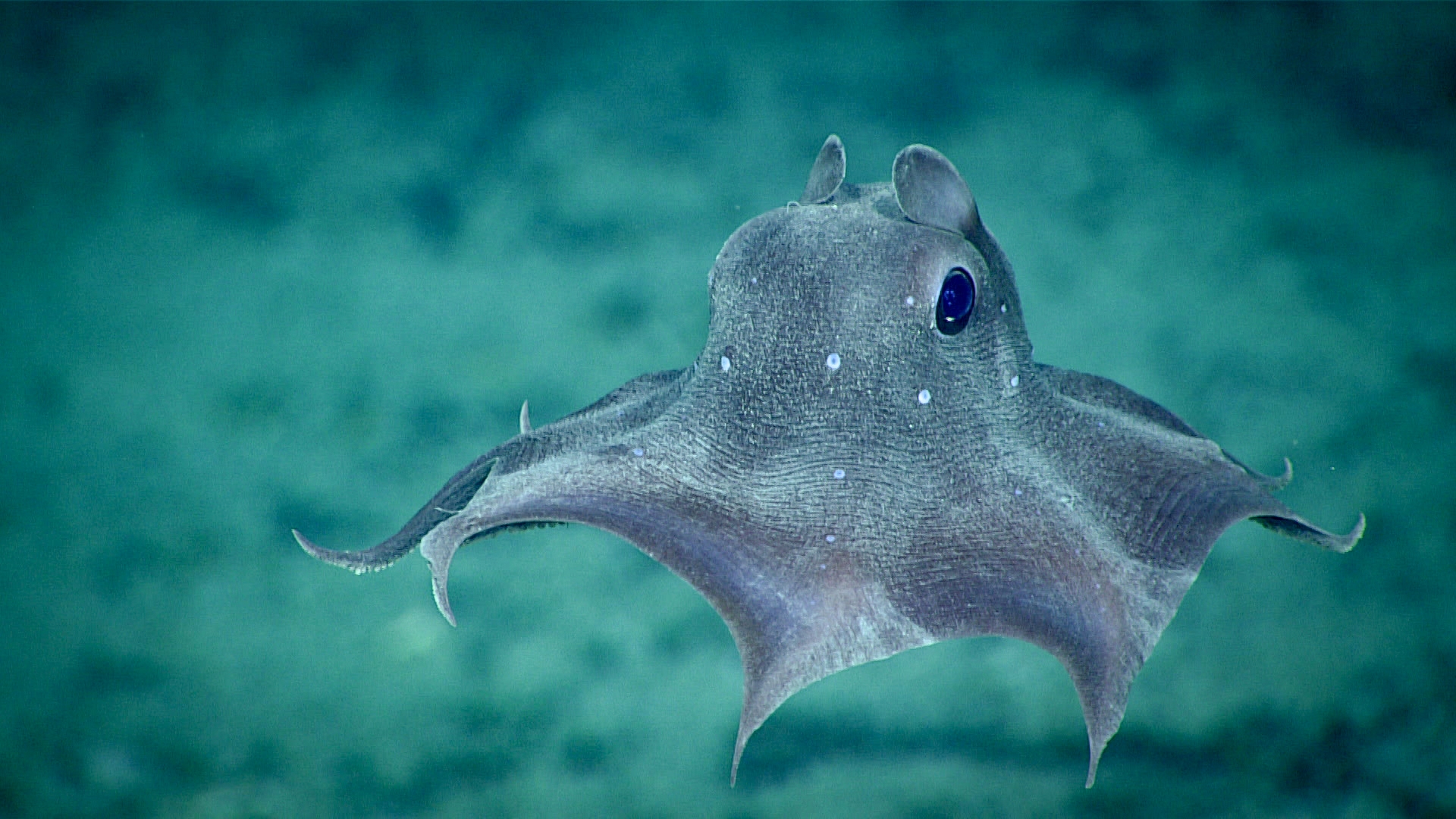

The popular imagination has traditionally seen the deep sea as barren plains of sand and rock, hostile to life. But the reality is completely different: it is teeming with life.

Dumbo Octopus © NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration

A safe haven for incredible biodiversity

The popular imagination has traditionally seen the deep sea as barren plains of sand and rock, hostile to life. But the reality is completely different. It is teeming with life: within the small portions of the deep sea where humans have ventured, the vast majority of species collected are new to science, including some that may not be found anywhere else in the ocean. In the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, where a great deal of mining is proposed to take place, it is estimated that up to 70–90% of the species collected are new to science.

In the deepest parts of the deep sea, life operates differently. The fauna lives under immense pressure, in a highly stable environment within a very narrow temperature range. Some deep sea species are long-lived and have slow growth rates. The Greenland shark, for instance, dives to around 1,200 metres and reaches maturity at around 150 years, with a lifespan of at least 270 years. Furthermore, scientists have discovered corals with lifespans ranging between 450 and 4,265 years, while some sponges can live an astonishing 11,000 years – the oldest living animals ever observed.

Untouched & unexplored

The deep sea – ocean areas below 200 metres – covers two thirds of the seafloor and makes up more than 95% of the Earth’s biosphere. It is one of the last unknown frontiers of scientific knowledge on Earth and still a mystery both in its wildlife and the ecosystems these species are a part of.

The deep sea harbours an incredibly rich variety of organisms, but it remains almost entirely unknown to science. Scientists discover new species in almost every dive to the ocean floor, the area which is home to around 98% of all marine organisms.

Chimaera © NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration

Life without sunlight

In the absence of sunlight, many deep-sea animals have developed the ability to emit biochemically produced light. Bioluminescence in the deep ocean is essential for communication, reproduction, defense against predators, and prey capture, and is believed to drive the emergence of new species. In parallel, deep-sea fish have developed highly sensitive vision, with the most complex eyes observed in vertebrates. In the freezing depths of the Southern Ocean, scientists have also discovered fish with an antifreeze protein allowing them to survive in temperatures below the freezing point.

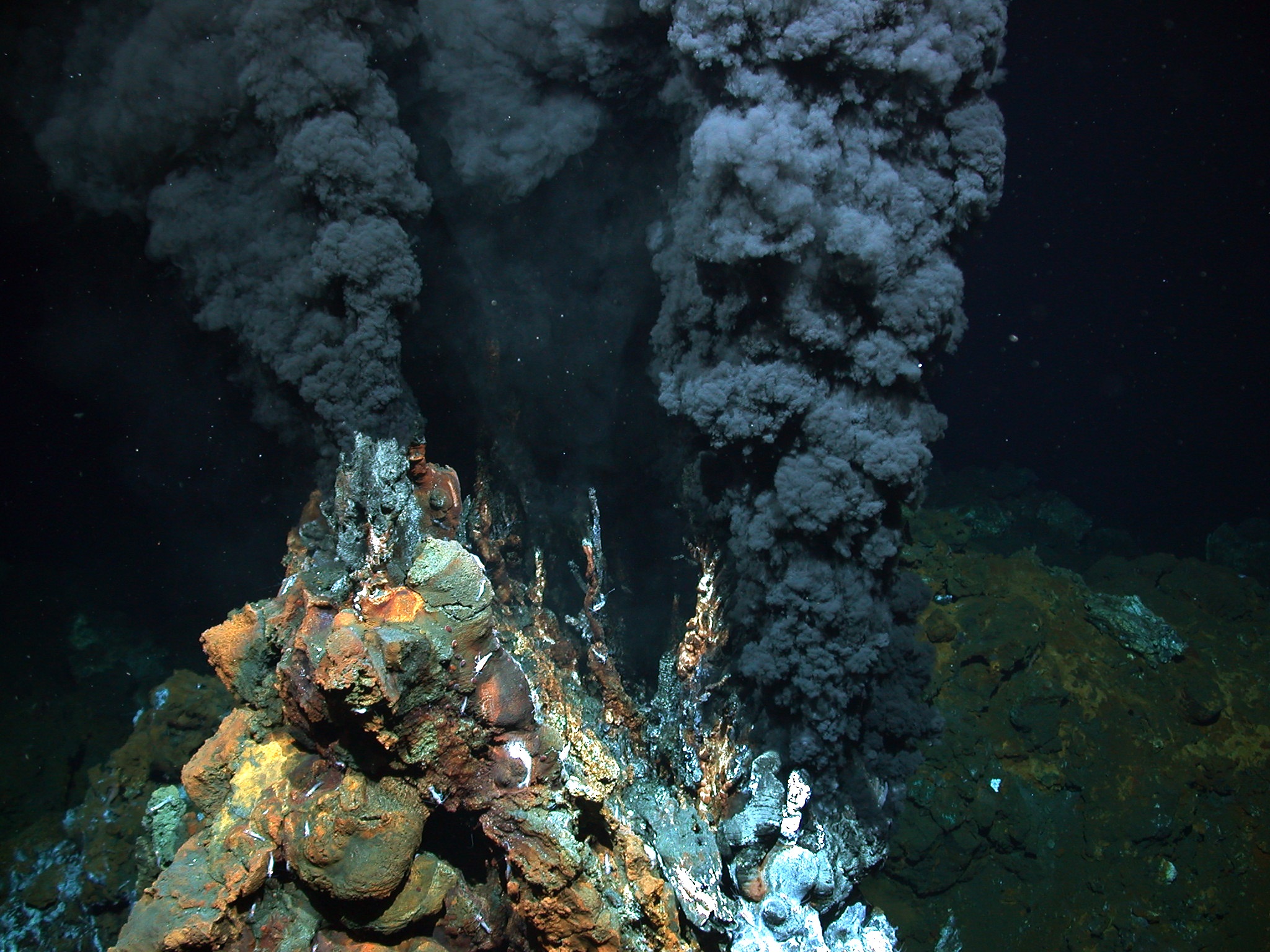

While photosynthesis cannot occur in the deep sea, the primary production of organic matter can still take place through a process known as chemosynthesis: some bacteria have the ability to fix mineral carbon and convert it into organic carbon, which can be used as a source of energy by other organisms. Tube worms, shrimp, mussels and many other species found aggregated around hydrothermal vents rely on chemosynthetic bacterial symbionts as a food source. As these organisms are in turn consumed by predators, chemosynthetic bacteria support an entire food chain.

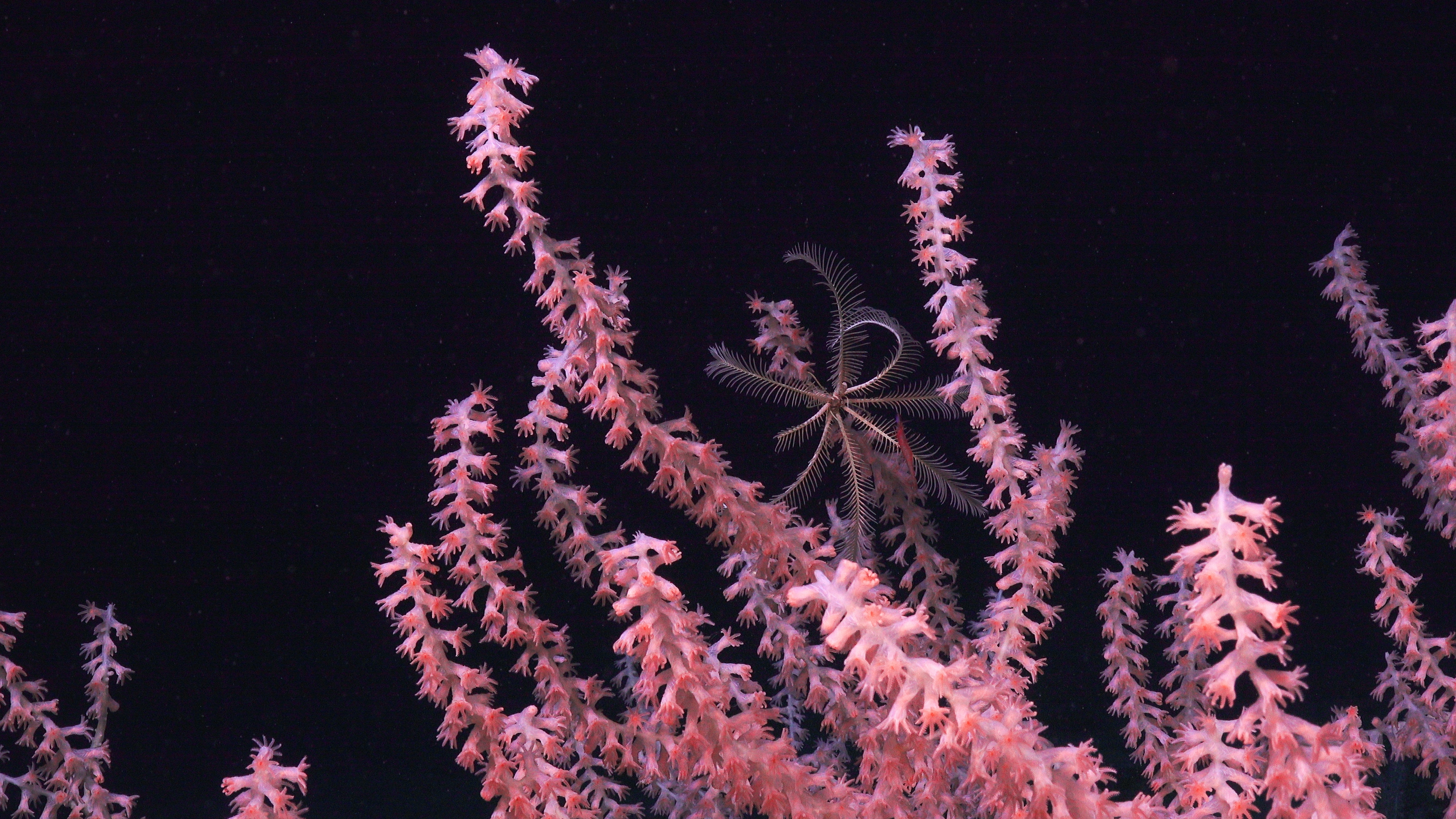

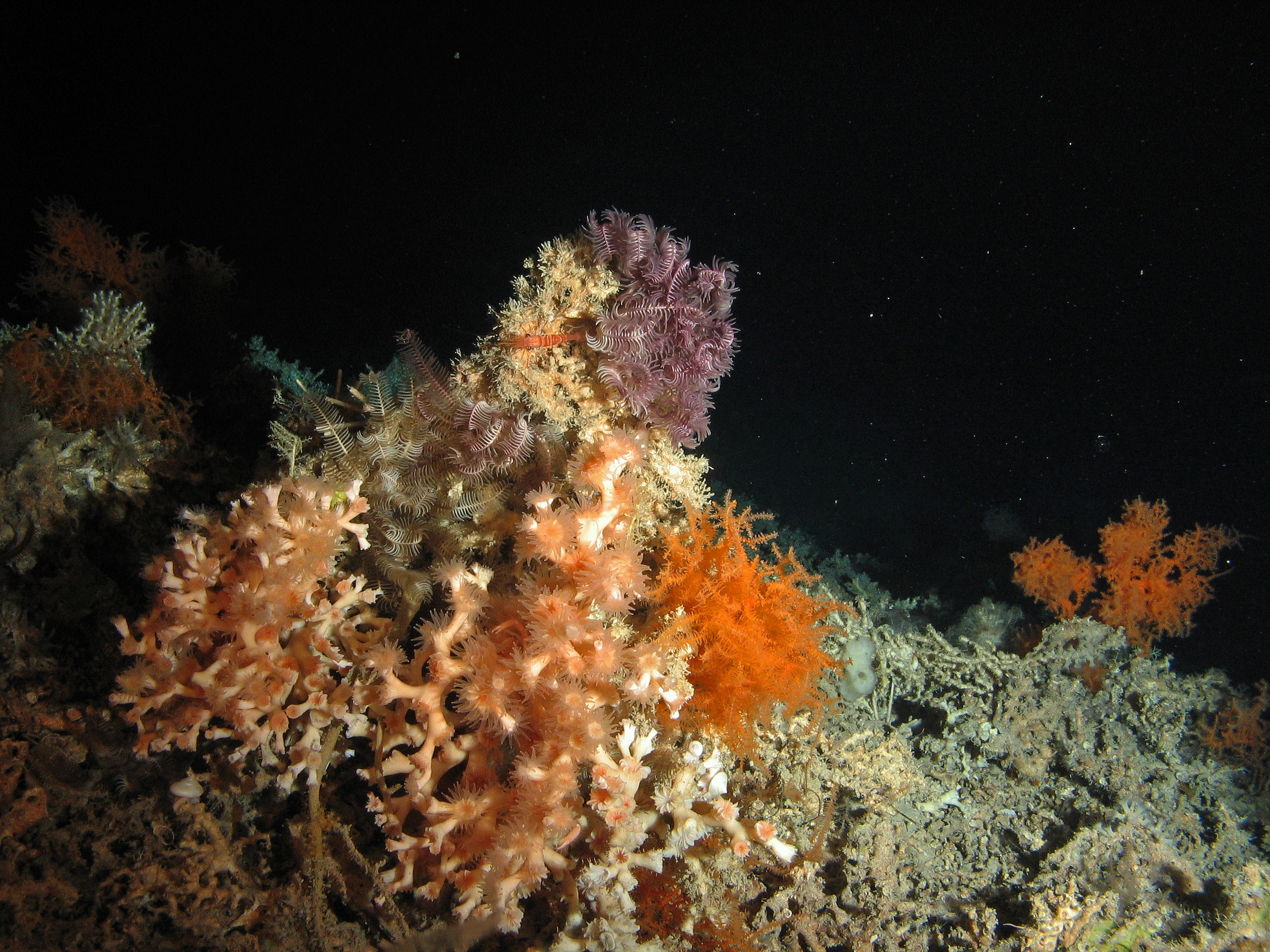

Seamounts – where cobalt-rich crusts would be harvested – harbour rich and diverse ecological communities, with corals, sponges, feather stars and an abundance of pelagic fish. They are important aggregation, breeding, foraging and resting areas for emblematic species such as whales, sharks, and turtles, and are used as landmarks by migrating species.

Role in the carbon cycle

The ocean, and the deep ocean specifically, plays a vital role in regulating the global climate and mitigating the effects of global heating. Almost the entirety of global carbon dioxide (98%) is dissolved in the ocean, which also stores 90% of the excess heat produced through greenhouse gases, supporting the survival for species across Earth.

While the vast majority of that carbon remains in seawater in dissolved form, a substantial fraction is buried in the seafloor sediments, with deep-sea sediments accounting for 80% of all the carbon stored in marine sediments. The burial of organic carbon in the sediment of the deep seabed is crucial in this and helps to regulate atmospheric CO2, maintaining the balance of our global climate. Deep sea sediments store up to five times more carbon than ocean sediments in shallow waters. The seabed's ability to lock in carbon exceeds that of terrestrial soil, with twice as much carbon-storage capacity in the top metre.

Carbon reaches the bottom of the ocean through a mechanism known as the biological pump: organic matter is formed at the ocean surface, mainly by phytoplankton, and either sinks to the ground or is actively transported through the food chain into the deep by fish, salps and other organisms. This way, organic material, including excrement and carcasses, settles on the seafloor where it is consumed and decomposed by local fauna and bacteria and buried into the sediment. A single dead whale, for instance, can contain up to 33 tonnes of carbon, which is eventually stored in the deep sea.

Despite scientific consensus on the fundamental role of the deep sea for climate regulation, much of its carbon cycle mechanisms, as well as its potentials, are in need of further study.

Our blue beating heart

As the world’s largest active carbon sink, the ocean is a natural solution to help combat climate breakdown. The deep sea plays an essential role, as it contains carbon accumulated over tens of thousands of years and will lock it safely away for generations to come if left undisturbed.

Bamboo Coral – Ivan Hurzeler and Deep Search 2019 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA, ROV Jason © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The dangerous "rush" towards the deep

As the deep sea holds vast amounts of valuable metals and minerals like cobalt, copper and manganese which are used in wind turbines and electric car batteries, it has become of great interest to mining companies. Proponents of deep-sea mining argue that mining in the deep sea is necessary to successfully manage the energy transition to a low carbon economy. However, deep-sea mining poses major threats to the health of our planet and is not without alternatives, making it both irresponsible and unnecessary to proceed.

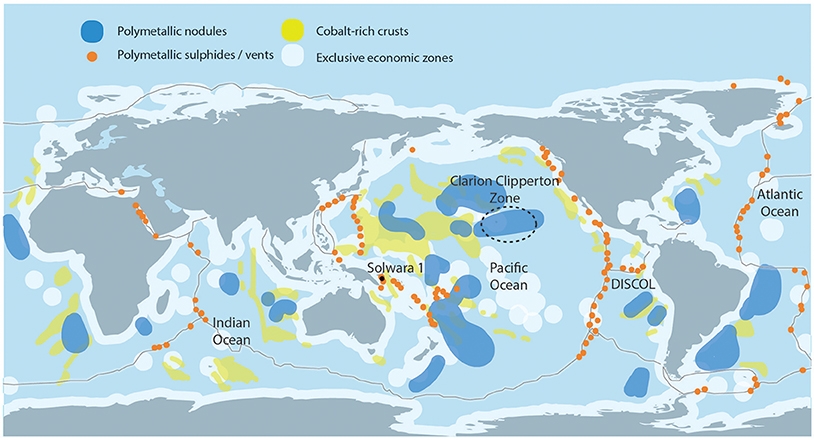

Worldwide, there are currently 31 mining exploration contracts, of which 22 have been awarded to governments or state-owned enterprises and 9 to private actors. Private actors have emerged as the lead proponents of deep-sea mining. Three corporations are particularly dominant in exploration activities headquartered in developed nations: The Metals Company, headquartered in Canada; UK Seabed Resources, a subsidiary of US-based Lockheed Martin; and Belgian corporation Dredging, Environmental and Marine Engineering NV. All deep-sea mining activities focus on three types of minerals: massive sulphides, ferromanganese crusts and polymetallic nodules.

A world map showing the location of the three main mineral deposits. Miller et al. (2018)

Severe risks for the environment

To extract minerals from the deep sea, mining companies are looking to scrape, dredge and cut out rare minerals and pump them up to specialised processing ships. Different extraction methods have been tested for the three main types of mineral resources. Polymetallic nodules lying on the seabed are retrieved by collector vehicles driven across the seafloor that use a jet of water to stir up the top layer of sediment and dislodge the nodules. The nodules and surrounding sediments are then sucked up into the collector, where the bulk of the sediment is separated from the nodules. The excess sediment is discharged at the back of the collector while the nodules and remaining sediment are pumped up through a pipe to the surface ship where they will be processed. On board the ship, nodules are separated from the slurry, and the wastewater is then released back into the water column.

Suspended sediments can travel hundreds of kilometres with ocean currents, potentially affecting organisms across vast swathes of the ocean. Additionally, light and noise adversely affect deep-sea species – noise from a single mining operation may reverberate for 500 kilometres, interfering with species' ability to communicate and detect prey and predators.

Potentially catastrophic impacts

Deep-sea mining will cause significant disturbances to the marine environment, including direct damage to benthic fauna, habitat destruction, pollution from sediment plumes and wastewater discharge, and noise and light pollution across the water column.

These disturbances will result in biodiversity loss, disrupt marine ecosystem functions and food webs, and potentially impact fisheries and disrupt the carbon cycle.

Queen Snapper © NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

“Sleepwalking” into a deep-sea mining era

Currently, there is no regulatory framework in place which would allow for large-scale commercial mineral exploitation in waters beyond national jurisdiction – also referred to as the Area. However, deep-sea mining can start on a commercial scale as soon as the international legal framework that will govern it – the Mining Code – is finalised by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and subsequent mining exploitation licences are granted.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is the intergovernmental body of 167 member states and the EU which regulates deep-sea mining. It was established under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and its 1994 Agreement on Implementation (1994 Agreement). UNCLOS gives the ISA the exclusive mandate to manage seabed minerals in waters beyond national jurisdiction on behalf of “mankind as a whole” and the exclusive right to issue exploration and exploitation contracts for minerals. The ISA also has the mandate to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from deep-seabed related activities.

In June 2021, in an unprecedented step, the ISA member state of Nauru triggered the so-called "two year rule", a provision of the 1994 Agreement, according to which the ISA must complete the adoption of the Mining Code within two years of such a request. This resulted in a rush within the ISA to finalise the Mining Code. States resisted artificial pressure exerted by the industry, but, with enormous pressure still being exerted by companies keen to start deep-sea mining as soon as possible, the threat is still present. There is great concern among policymakers and other experts that humanity is "sleepwalking" into a deep-sea mining era - one we do not need and cannot afford.

Dubious business

The ISA is not fit for purpose: it has never rejected an application for a deep-sea mining exploration permit. Meetings take place secretly behind closed doors without detailed meeting minutes being shared.

The ISA is also highly intertwined with corporations, both through lobbying and by its institutional structure. Concerns have been raised that in the long-term, the ISA is to be funded by revenues from the deep-sea mining contracts it issues – an apparent conflict of interest. Finally, the involvement of civil society in the ISA’s decision-making processes is limited and has been widely criticised.

Black smoker in 2,980 metres of water on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge © MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen (CC-BY 4.0)

A global movement against deep-sea mining

An increasing number of countries have renounced the exploitation of the deep sea. The Island State Palau became the first country to advocate for a moratorium. Fiji, Samoa, Chile and Micronesia joined the moratorium alliance shortly after. On 27 October 2022, New Zealand called for a “Conditional Moratorium”. Four days later, Germany shifted its standpoint to a clear opposition, advocating for a “Precautionary Pause”, followed by France, which “supports the ban on all exploitation of deep seabeds”. On 30 October 2023, right at the beginning of ISA’s annual meeting, the UK declared its support for a moratorium. This adds to the list of 27 countries opposing deep-sea mining.

The European Commission also called for deep-sea mining to be prohibited and the European Parliament has called on EU member states and the Commission to support a moratorium on deep-sea mining until scientific gaps have been properly filled and deep seabed mining can be managed “to ensure no marine biodiversity loss nor degradation of marine ecosystems”. Countries including Brazil and Italy have stressed the need for robust, science-based regulations on deep sea mining, but have stopped short so far of calling for an outright moratorium or ban.

Along with states, more than 700 marine scientists and experts signed a statement recommending a pause at least until sufficient and robust scientific knowledge is gathered, and more than 250 parliamentarians from over 50 different countries signed a call for a moratorium. In September 2021, a motion calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining was adopted with almost unanimous support by the IUCN World Conservation Congress. Additionally, major companies, as well as banks and financial institutions, have taken a stand against deep-sea mining. This includes car manufacturers BMW, Volkswagen and Volvo, global electronics corporations Samsung and Philips and technology giant Google, which have publicly committed not to purchase minerals from the deep seabed, throwing doubt on the business case for commercial mining.

This is a golden opportunity to stop the devastation before it even begins – one we cannot afford to miss.

Steve Trent, CEO and Founder of EJF

Rattail fish © NOAA OER/Global Explorer

Our final chance to defend the deep

Little do we know about the deep sea, but all scientific observations gathered so far indicate that it is crucial for the health of our planet. The deep sea hosts a myriad of living organisms essential to maintaining our global food supply, supporting rich biodiversity, and locking away CO2 for millennia. Mining this vital part of our ocean could be catastrophic, with potentially global and irreversible implications.

An ever-increasing number of scientists, non-governmental organisations, businesses, policymakers, states and intergovernmental organisations like the EU have stood up to strongly oppose deep-sea mining. However, more support is needed to stop the rush to the Mining Code, primarily driven by industry and negotiated within a deeply flawed institution. The ISA has shown itself unfit for purpose, with troubling displays of conflict of interest and a significant lack of transparency and democratic decision-making.

In order to achieve zero emissions, we need to scale up efforts towards the green energy transition. But to open up the deep sea to excessive and devastating commercial mining cannot be the solution; nor can it be presented as the only viable way forward. On the contrary, deep-sea mining threatens to accelerate the catastrophe we are facing today.

Only national negotiators can save the deep ocean now. The world’s message to them is clear - listen to the growing tide of voices calling for a stop to deep-sea mining before it begins.

A way forward

According to proponents of deep-sea mining, the exploitation of the seabed is necessary to cover future mineral demand. However, projections about future demand of minerals are highly uncertain and give insufficient consideration to the role of recycling and recovery of metals. In countries such as the UK and Germany, a linear “take, make, waste” economic model, built on ever-increasing resource extraction to meet our endless consumption, means we currently require up to three planet Earths.

If we want to reduce dependencies on new raw material sources and stop increasingly excessive mineral exploitation, a fundamental transformation of the global economy is essential: from a linear model towards a truly sustainable and circular economy – a model of production and consumption which seeks to ensure our economies are designed, our products made, and our consumption aligned within planetary boundaries.

Cold-water corals off Ireland in 750 metres of water © MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen (CC-BY 4.0)

SIGN UP FOR OUR EMAILS AND STAY UP TO DATE WITH EJF